From user experience to competency model design - Margherita Bacigalupo and EntreComp

Steven Forth is co-founder and managing partner at Ibbaka. See his skill profile here.

Ibbaka is carrying out design research into competency models and as part of this work we have been having conversations with people around the world about how they approach this important work.

You can read more about this design research here.

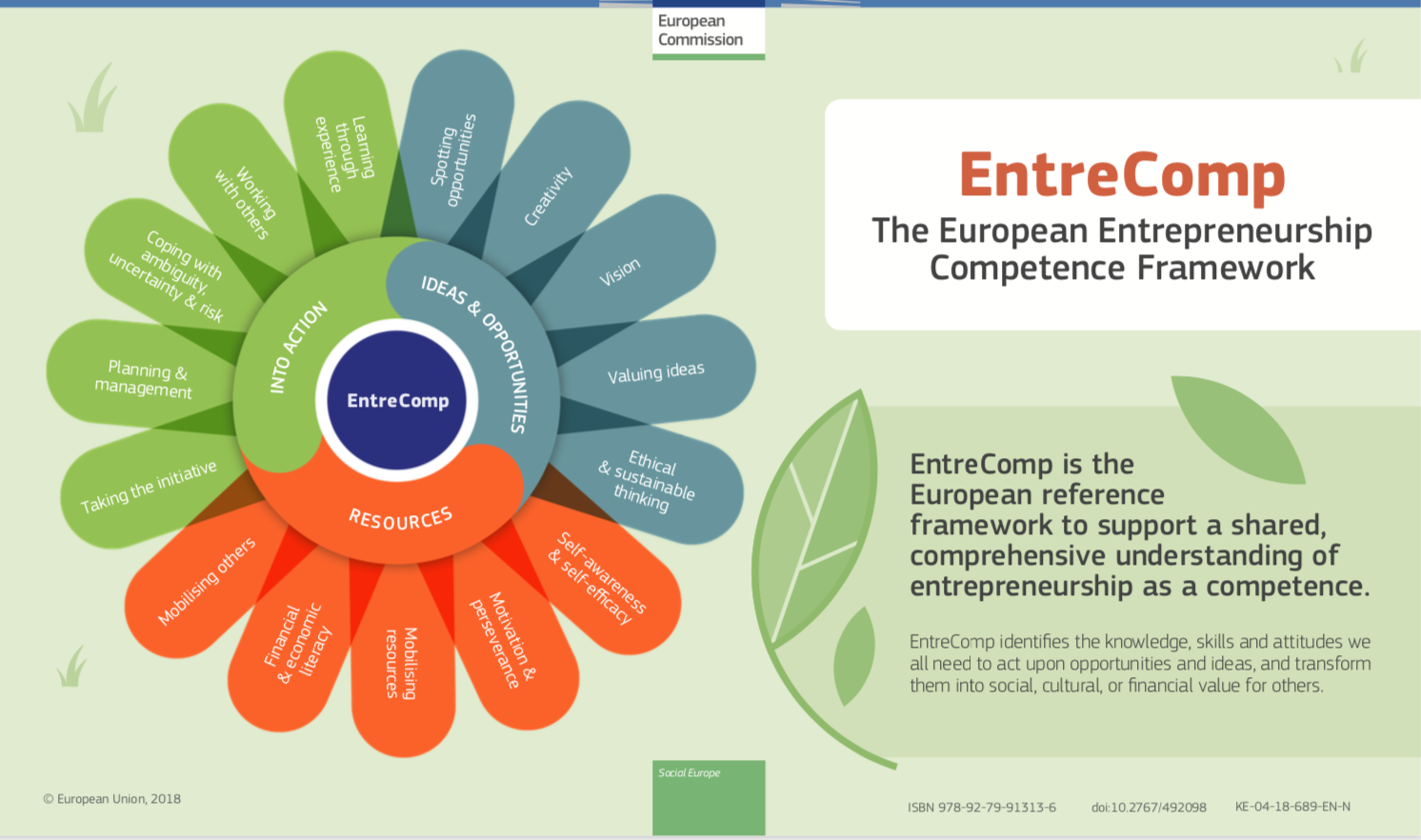

Margherita Bacigalupo is a Research Fellow at the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission’s Science Service. She led the development of EntreComp, the European Reference Framework for Entrepreneurship, which the JRC has developed in collaboration with the European Commission Directorate General Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion.

We spoke with her in May to learn more about her work.

Ibbaka: Can you tell us more about your career and how it informs your approach to competency model development and application?

Margherita: I am a designer and have studied computer interaction. I did my PhD on human-robot interaction with a strong user-centered design approach. The first part of my career was about designing interfaces; more futuristic in the field of air traffic control and more pragmatic and ready-to-use when I was working in the manufacturing industry.

In 2015 I moved to the European Commission, to the Joint Research Centre which is the research arm of the Commission. When I moved there, I started working on entrepreneurship as a key competence for lifelong learning. I had no experience in this field, so the only thing I could leverage was my user-centered design background. I always enjoyed changing fields and then applying the same methodology to a new field.

At the Joint Research Centre, there was a already a methodological approach established with respect to the creation of a competence framework. It consists of two main strands of work; the first stand entails desk research, literature review, collection of inventories of practices, case studies. The second strand relates to the formulation of a proposal through iteration with stakeholders aimed at consensus building.

One thing I brought into this process was user personas and scenarios. At each stage of the evolution of the framework, I envisioned possible users, stories, and narratives to try and see if these competencies were framed in meaningful ways. I used methods that I used to use in my interface design to deepen my own understanding of the domain.

Ibbaka: You brought skills and experiences in user-experienced and user-interface design to your work on the competency model. What other skills did you need to augment those skills? Were there other skills to learn?

Margherita: Very many other skills. On the one hand, I would say analytical skills were important. The capacity to map and structure the different competencies was important – analytical and synthetic skills came into play because you can analyze entrepreneurship until the end of your days without reaching a final point.

Another skill that was important was the ability to relate to stakeholders. In the world of education and training, the Commission has no regulatory power, only a supporting function. The implementation of these competence frameworks is the responsibility of the Member States who decide if and how to embed this in their school curriculum.

In competency model development it is critical to bring in the right people at the right time and to have enough iterations to create a consensus. For example, in our case it was essential to bring in view of countries that have different entrepreneurial cultures and business practices.

The role of the designer is not to impose a solution. Rather the designer elicits needs and shapes solutions to serve the purpose of the users. This is more of an attitude and not really a skill. I knew nothing about entrepreneurship when I started, and this helped me be humble when approaching the task.

Another set of skills and competencies that I had to deploy in these exercises was self-motivation, perseverance, and the capacity to persist despite the difficulties. This is not easy work and it is easy to get discouraged.

Learning to learn is a competence that is described in one of our frameworks and I think that this is something that you need to embrace in such an endeavor. You must be able to learn along the way.

Ibbaka: A lot of time, effort and passion has been invested in developing EntreComp, how are you seeing it being applied?

Margherita: Beyond expectation. This framework was born with a broad spectrum of users in mind and is there to support actors at Member State level embedding these competences across their lifelong learning ecosystems. This is one of the main purposes. By making competence frameworks available the Commission helps Member States in transforming education systems towards competence-based approaches that go beyond the knowledge-based approach of much traditional education. We define competencies as the instantiation of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in real situations. This connects knowledge to its application.

It is different from learning about history for the sake of learning history or having mathematics as a silo. There is a transformative intention behind the generation of competence frameworks. One example is the pioneering framework for foreign language learning by Council of Europe . This framework has completely reshaped the training of language across Europe and beyond. There is now a common approach to teaching and learning languages across Europe.

One issue that cannot be dismissed is the measurement of the level of competence in the population and its progress over time. For instance, at the European level, the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) summarises indicators on Europe’s digital performance and tracks the progress of EU countries. Its human capital dimension uses the European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp) as the conceptual basis for the Digital Skills indicator which assess whether the citizens in Europe have a basic level of digital competence.

For me, the most unexpected way in which EntreComp was used was in academia. This is especially in the UK, which has pioneered the description of entrepreneurship as a competency. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education has defined two different competencies: enterprise and entrepreneurship. Enterprise competencies are the broad ones used to manage and operate a business. Entrepreneurship is more focussed on innovation and business creation.

EntreComp is bridging two different worlds. The world of business and the world of taking initiative to create something that is not necessarily of a commercial nature. Social innovation is part of EntreComp.

One of the most striking uses I saw is by Maria Sourgiadaki, a Vocational Education teacher in Crete, Greece, who created a visualization of the framework that she calls the ‘EntreComp Giant.’ The trunk is made up of the ideas and opportunities competences. The head and limbs are the resources. The hands and feet represent the into action competences . Going from the heart to the limbs, her students learn they to turn their value creating ideas by into action. She mapped this for students and adult-learners to reflect on what they are learning and why they are learning it.

Ibbaka: As you think about EntreComp, does it need to change over time and if so, how will it change over time?

Margherita: We were expecting to receive requests for changes and updates because of our experience with the DigComp that is now reaching its fourth revision. DigComp study started in 2010 and was first published in 2013. The fourth release, aka DigComp 2.2, is enriching the framework with . example of knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) statements . These are meant to reflect changes that technology has seen. DigComp 2.2. will have a focus on artificial intelligence, on user data and on remote. Aspects of work that 10 years ago were not so critical.

If there is need and demand, then the Commission updates its frameworks to ensure they remain relevant and useful. Now that DigComp comes up with examples of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, I can imagine that, in one-or two-years time, stakeholders will ask us to produce examples of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in an updated release EntreComp..

We have another framework called LifeComp, that covers personal, social, and learning to learn competences. This framework does not have learning outcomes statements nor knowledge skills and attitudes statements. It is quite possible that there will be a request from the community of stakeholders who use the learning outcomes of EntreComp and the KSA statements of DigComp, to unpack the personal, social, and learning to learn competencies and update the framework with learning outcomes and KSA statements.

All this is done in dialogue with the community of users.

Ibbaka: Is there a formal model for how input is made or is it more informal?

Margherita: Bear in mind that European Competence Frameworks are not standards. The Governance model for them is open. Responsibility is shared between a policy owner at Commission level and a team of researchers at JRC level, who are partner in the development and support to implementation of the different competence frameworks.Beyond the responsible actors there are internal and external stakeholders. Internal stakeholders are other services of the European Commission and its agencies. External stakeholders are diverse they include international organisations, national, regional and even local actors that play a role in lifelong learning systems they include representatives of the public, private and third sector alike

There is a variety of actors, associations and networks in constant dialogue with the Commission. An important group of stakeholders are practitioners, such as teachers and trainers. Often the pioneer users if the Competence frameworks are winner of EU grants or projects funded with different schemes, such as Erasmus+, Cosme grants, or Horizon research funds. They play a fundamental work in bringing the frameworks forward. As an example I can mention the EntreCompEdu Eramus+ project, which has created a framework, targeting teachers and educators that defines the competences they need to teach and empower learners to develop and deploy EntreComp competences.

Stakeholder engagement has been done in different ways. Before the pandemic, we used to invited stakeholders to come to Seville for a in presence discussion. Then we leveraged an official instrument of the European Commission called the ‘open method of coordination .’ We would meet and present progress on the development of competence frameworks to Member States. Many of these interactions were physical and the pandemic has generated a new sort of interaction and opened the way for more stakeholders to participate. For instance, the revision of DigComp 2.2 is pending through an online platform to which anybody can join and have their say.

Ibbaka: If you were speaking to yourself as you were when first coming into the role of competency model designer, or to a young person getting into this line of work, what advice would you have for them?

Margherita: Do not give up. It will be crazy at times, but it will make sense in the end. I have been advising a number of my colleagues on the development of competency models, and this has always been my key message. It seems impossible to embrace competences, especially overly broad competences, so it is important to trust your capacity to make sense of things that are not there. People need to be motivated that they can do it and not be put off by the difficulty of the task.

I am very happy to say that colleagues I have discussed at length with in how to build competence frameworks have just made available for peer review two frameworks aiming at supporting professionalization pathways for policy makers job and researchers working to inform policy design. Anyone can provide feedback on them until the 8th of September 2021, which you can do by following this link.

Ibbaka: Looking out beyond the world of competency models, what are other things we can be doing to help people understand their potential, get recognized, and find meaningful work to build their careers?

Margherita: I think that competency models have a huge power in describing things. When I think of the entrepreneurial competencies, there are 15 in total. We should not expect anyone to master that many competencies at an expert level. In general, the more advanced the competence level, the narrower the competence set you have at that level.

European competence frameworks are not normative, but descriptive. It is important that people choose according to their ambition and preferences. There is a danger in describing things in boxes. Some people will think that all you need to do is to tick some of the boxes. It is the other way around. Frameworks allow for different paths that let you explore without getting lost. You can take a path that brings you towards a participative leadership kind of role. No matter what your domain is. Or you can take another path that leads to specialization and deep knowledge.

I do not like systematic documentation of the work that I do, I have to fulfil the task, but what I like is to create something new. Should I live a life of sorrow saying I am not good at documentation or should I rather try to partner with a colleague that is good at that? Does my employer want me to do two completely different tasks – one that I am particularly good at and one that I struggle with? This is important for productivity and being at ease with the choices we make. Because at the end of the day competence frameworks map a landscape of possibilities but the journey one makes is personal and unique.

Ibbaka posts on competency models and competency frameworks

From user experience to competency model design - Margherita Bacigalupo and EntreComp (this post)

Competency framework designers on competency framework design: The chunkers and the slice and dicers

Competency framework designers on competency framework design: Victoria Pazukha

Design research - How do people approach the design of skill and competency models?

The Skills for Career Mobility - Interview with Dennis Green

Lessons Learned Launching and Scaling Capability Management Programs

Talent Transformation - A Conversation with Eric Shepherd, Martin Belton and Steven Forth

Individual - Team - Organizational use cases for skill and competency management

Co-creation of Competency Models for Customer Success and Pricing Excellence

Competencies for Adaptation to Climate Change – An Interview with Dr. Robin Cox

Architecting the Competencies for Adaptation to Climate Change Open Competency Model

Integrating Skills and Competencies in the Talent Management Ecosystem

Organizational values and competency models – survey results