The opposable mind and pricing - Applying Roger Martin to critical pricing decisions

Steven Forth is a principle at Ibbaka and valueIQ. Connect on LinkedIn

At Ibbaka, we start most engagements with Roger Martin’s Strategic Choice Cascade, which we have adapted for pricing.

Doing this work, we often run into leadership teams with goals that seem to be contradictory. Some examples of common pricing goals that contradict each other.

1. Maximize Profit vs. Maximize Volume

Goal A: Maximize unit margin and overall profit per sale.

Goal B: Maximize sales volume or market share through low prices.

Raising prices to increase per-unit profit usually suppresses demand, while cutting prices to drive volume typically reduces margin and can delay profitability.

2. Premium Positioning vs. Price Leadership

Goal A: Position the offering as high-end or luxury with high willingness-to-pay.

Goal B: Be the lowest-priced option in the category.

Premium brands rely on higher prices to signal quality and exclusivity, whereas “everyday low price” strategies anchor customer expectations at the budget end of the market.

3. Short-Term Cash vs. Long-Term Brand Equity

Goal A: Generate immediate revenue via aggressive discounts or promotions.

Goal B: Protect long-term brand value and customers’ reference price.

Heavy discounting can create a deal-dependent customer base and permanently lower perceived value, undermining efforts to sustain a strong brand and healthy price points later.

4. Stable Relationships vs. Frequent Optimization

Goal A: Maintain price stability to build trust with customers and channel partners.

Goal B: Continuously optimize prices (e.g., dynamic pricing) to capture every bit of willingness-to-pay.

Frequent price changes can erode trust and create perceived unfairness, while stable, predictable prices limit the ability to adjust quickly to demand shifts or cost changes.

5. Barrier to Entry vs. Healthy Margins

Goal A: Use very low prices to deter competitors or gain rapid share (penetration / quasi-predatory behaviour).

Goal B: Maintain healthy, sustainable margins that fund innovation and service quality.

Pricing low enough to discourage entrants often requires sacrificing margin for an extended period, which conflicts with objectives tied to near-term profitability and return on capital.

Do these have to be contradictions?

In his 2007 book The Opposable Mind, Roger Martin argues that the strongest strategic choices are those that integrate contradictory ideas or goals. Integrative thinking is defined as the ability to face the tension of opposing ideas and generate a new idea that contains elements of each but is superior to both.

According to Martin, integrative thinking relies on looking at as broad a context as possible, mapping the causal relations in a problem, and refusing to let go of the tension caused by the contradiction.

Can this approach be applied to pricing?

Let’s pick one of these challenges and see what might be possible.

Can one maximize profit and maximize volume at the same time?

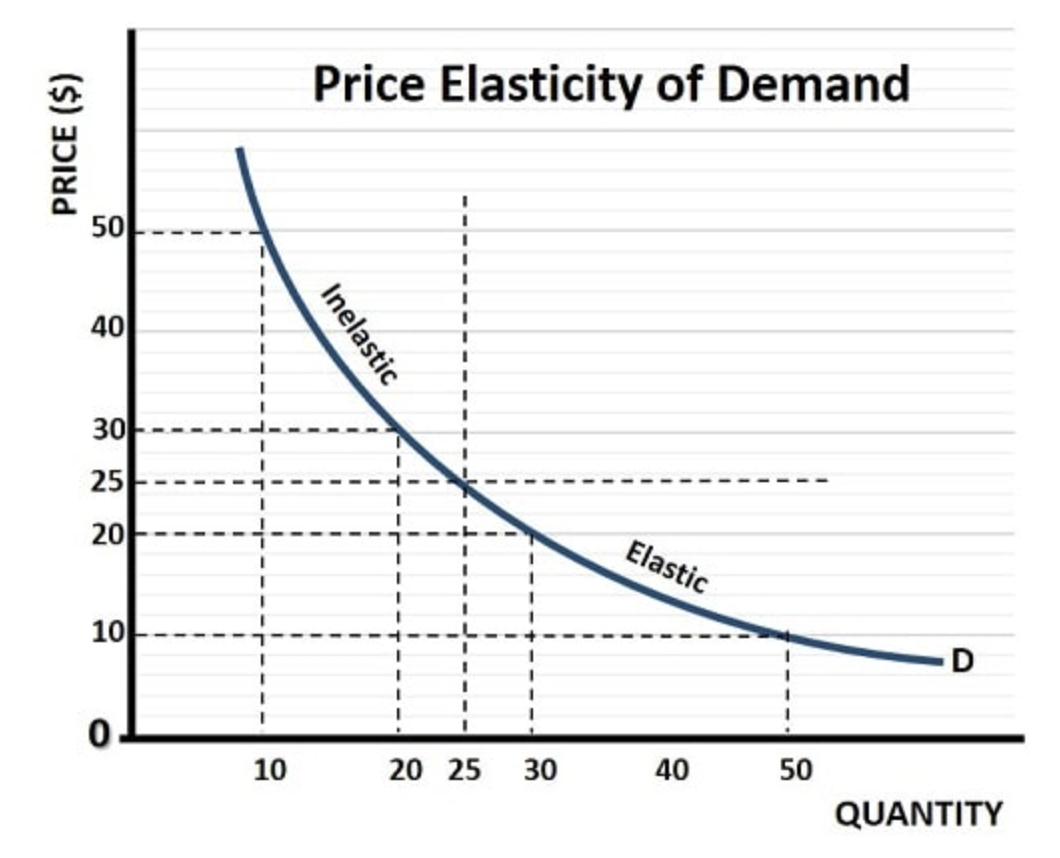

The conventional wisdom is that one must trade off profit optimization for volume optimization. It is a pricing truism that the profit-optimizing price is different from the volume-optimizing price. This reflects the assumption that the price elasticity of the demand curve slopes down to the right. A typical price elasticity of demand curve is shown below.

The shape of the curve matters here. This curve is convex, meaning that the price elasticity of demand increases with volume. Buyers are less price sensitive when buying only a small quantity, but become more price sensitive as volumes increase.

This is not the whole story, though.

In addition to price elasticity of demand, one has to consider cross-price elasticity, the tendency of a buyer to switch vendors in response to a price differential.

Cross price elasticity and price elasticity of demand interact to create four typical market dynamics. You can read more about this here: Understand your market's dynamics before you set your pricing strategy.

Market Dynamics: How Price Elasticity of Demand and Cross Price Elasticity Interact

Cases where economic value (as measured using a value model or Economic Value Estimation) can increase non-linearly with consumption (the value curve can be convex). With value-based pricing, this can lead to situations where demand goes up with price, especially if there is low cross-price elasticity.

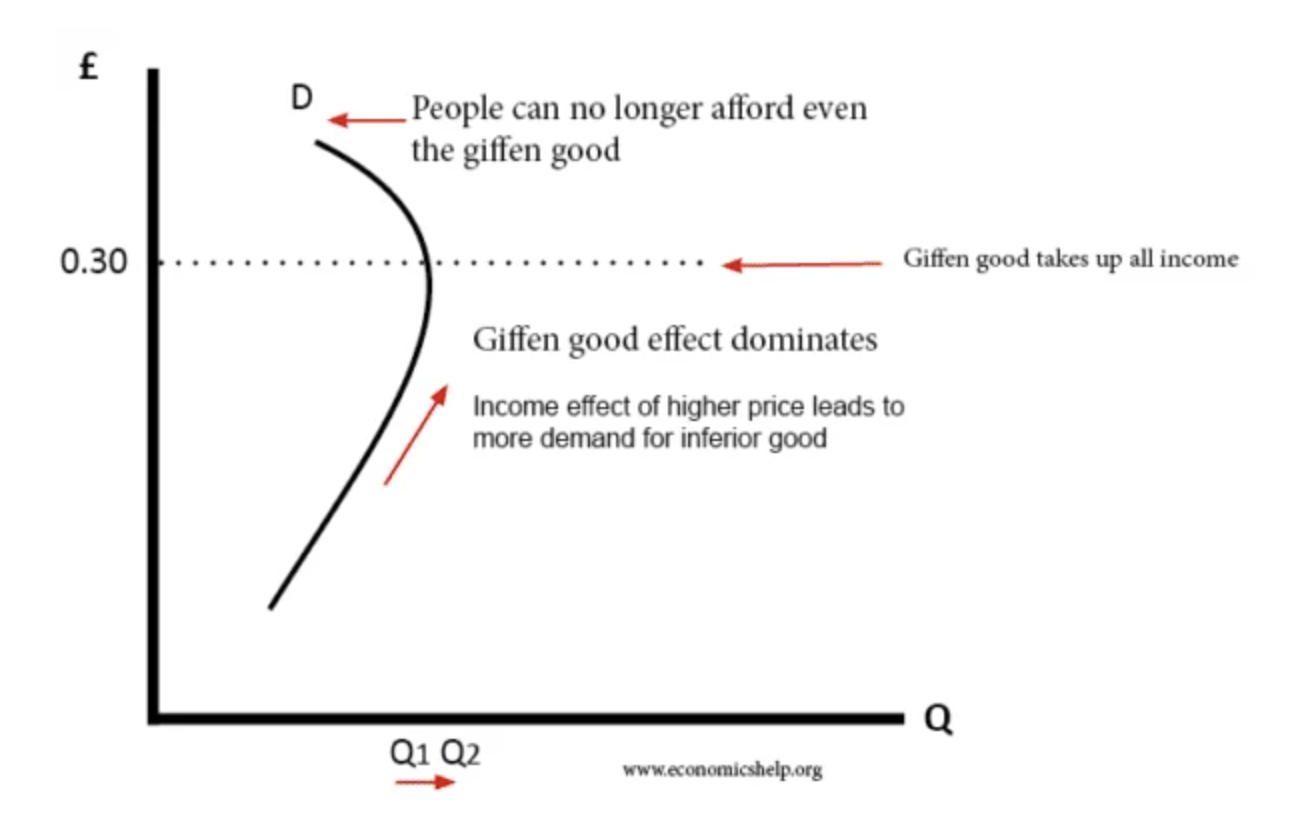

This leads us to a new perspective on what are called Giffen goods. Traditionally, these are goods that are strongly inferior staples (like very cheap bread, rice, or potatoes for the poorest consumers) where a price rise makes people effectively poorer and pushes them to consume more of the cheap staple and less of better foods, so quantity demanded rises with price over some range. The upward slope comes from the income effect outweighing the substitution effect; this pattern generally appears only for very low‑income consumers and over a limited price band, not for the whole market. (The effect is named for Scottish economist Robert Giffen, who observed it in poor households’ food purchases in the late 19th century. It was documented by Alfred Marshall in his 1890 book Principles of Economics.

Certain AI-enabled technologies can act like Giffen goods.

Companies feel they must buy AI (and budgets are limited, so they are effectively ‘poor’)

The AI is less capable than a highly qualified human (i.e. it is in some way an inferior good)

Higher spending on AI leads companies to spend less on highly qualified humans

This leads companies to increase spending on AI as the price increases

The integrative thinking resolution of the profit-volume tradeoff

The integrative thinking resolution of the profit-volume tradeoff is to

Operate in markets with low cross-price elasticity and low price elasticity of demand

Invert (or at least flatten) the price elasticity of demand

How to do this?

Design systems where greater use gives greater value

Operate in spaces where your solution acts as a Giffen good

The trade-off between profit and volume can be resolved in certain cases. Design in value. Make the product a necessity. Drive a higher-priced substitute out of the market (this sounds a lot like Clayton Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, but that is a story for another day).

Note that this approach can also address the tradeoff between price and market share.

Conclusion

Integrative thinking is no longer optional in B2B SaaS pricing; it is the only way to escape false tradeoffs and turn tensions like profit vs. volume into a durable advantage.

Leaders who win will be those who deliberately design offerings, value models, and customer relationships so that increased usage creates disproportionate value and makes their pricing feel not just acceptable, but inevitable.

If your current pricing debates are still framed as either/or, it is time to revisit your choices, rethink your market dynamics, and build a pricing system that makes those old contradictions obsolete.

Roger Martin’s books relevant to this post

Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works (with A.G. Lafley) - 2009

The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking - 2007

Creating Great Choices: A Leader’s Guide to Integrative Thinking (with Jennifer Riel) - 2017

Navigating the new pricing environment brought by AI agents? Contact us @ info@ibbaka.com