Seeding - Assessing - Evolving Skills

Steven Forth is co-founder and managing partner at Ibbaka. See his skill profile here.

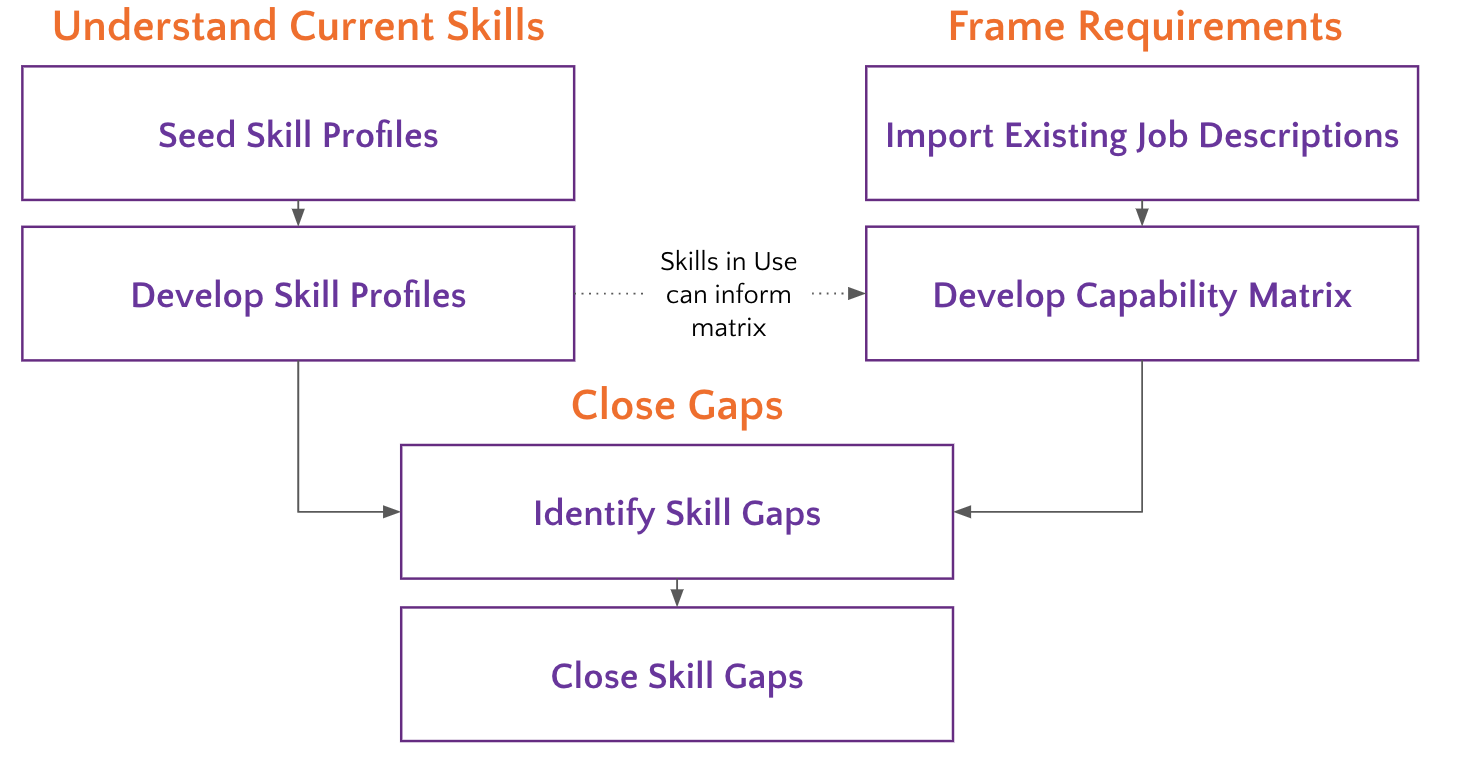

One of the root use cases for a skill and competency management platform, like that offered by Ibbaka Talent, is to understand what skills are present in an organization, at what level and how they are being used. When we work through this with customers, there are a number of issues that come up. It is worth considering these together to understand how to create value for all users at each step of the roll out.

The questions that come up are

Where do the initial set of skills come from?

How will a person’s skills be assessed?

How will the skill profiles evolve over time and stay current?

Let’s work though each of these.

Where do the initial set of skills come from?

It is disheartening to come to a skill profile and find it empty, whether it is one’s own or that of someone else. In the trade this is referred to as the cold start challenge. It can slow down a skill and competency management program right out of the gate. There are several effective ways to address this.

When a competency model is in play, begin by connecting people to jobs and roles. You will need to have access to competency models that cover most of the people in first roll out. It does not have to cover all of their roles, and the role does not have to be complete (inviting people to augment roles with their own skills is a powerful tactic), but there has to be enough there so that every person will have one role attached to their profile. Where do these role descriptions come from? Well, Ibbaka can quickly create a competency model based on your existing job descriptions. They may not be perfect but they provide a place to start. Another option is to buy a skill library. These can easily be imported into Ibbaka or linked by APIs. Ibbaka itself is making available a growing set of Open Competency Models that you can adopt and adapt as necessary. There is no charge for this.

Not every organization wants to start with competency models. There are good arguments to start fast and move light by jumping directly to use of skill profiles without a competency model in place. There is still the cold start issue do deal with though.

One approach is to look to another system that may have information on skills. The obvious candidate here is LinkedIn. Ibabka Talent can, with each individual’s permission, add their LinkedIn skills to Ibbaka Talent. LinkedIn has a great deal of meaningful data about skills, jobs and roles that can be used to build individual skill maps. Once you have the individual maps, they can easily be aggregated.

Another approach is to simply upload an individual’s résumé. Yes, résumés are notoriously out of date and inaccurate, but remember, the goal here is to seed the profile with just enough information to get the ball rolling. Other documents that may be relevant here are patent applications, project documentation or other writing.

A third approach is skill interviews and skill surveys. Skill interviews can be incredibly revealing, one can go deep into questions like what skills are connected to specific goals, who people work with and what skills are used together, and how people acquire and pass on skills. The problem with skill interviews is that they don’t scale and there is a lot of work needed to interpret from the interview into a profile. Interviews are an important tool, but they are best used with leaders, thought leaders and influencers. In this case, one can kick off the program by directing people to a rich profile of a person they respect, along with some guidance on how to use another person’s profile as a reference point in building their own profile.

Related to the skill interview is the skill survey. Design of skill surveys requires a lot of thought. As with any survey, the person taking it should get value from the process of doing the survey and follow on value once the survey is completed. Making this survey approach scalable also requires an integration between the survey tool and the skill management platform.

How will a person’s skills be assessed?

It is important to assess skills. Skilled performers can have far more impact on team and organizational performance than the average person. The deep thinking on this comes from Tom Gilbert’s classic book Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance. Understanding what we can do to bring average performers closer to great performers is the key activity in performance design. Skill and competency management is a foundational part of this, but to be meaningful one needs to be able to assess proficiency on skills and competencies.

There are basically eight approaches to skill assessment. Deciding which to use is in part a cultural decision and in part dependent on how much you are willing to invest.

Self assessments - This should not be ignored or discounted. People’s own view of their skills is critical to how they understand and portray themselves.

Manager assessments - Use of manager assessments is culture dependent. They are generally no more accurate than self assessments, but finding places where there is a divergence can help people in this critical relationship to better understand each other.

Peer assessments - these are generally the most powerful form of assessment. They are more accurate than self or manager assessments. But there are some caveats. The peers have to understand and participate in the work (this is why Ibbaka Talent assess in the context of teams and project teams). Consistent biases in team assessments have to be identified and compensated (examples are teams all giving each other high ratings, or scapegoating). The peers have to have some understanding of the skill. When the skill is highly specialized, expert assessment can be more relevant.

Expert assessments - when available these can add critical insights, especially for highly specialized skills where the average person is not really able to make an assessment.

Testing - there are some skills where formal tests provide real insight into the level of knowledge. Be careful though, test results do not always predict performance.

Evidence - there are many forms of evidence that can be used to demonstrate a level of expertise. The most important are work products such as reports, patents, designs, white papers and so on (the same documents one might use to seed a skill profile). The challenge here is that most work is done in teams and it can be difficult to untangle the contributions of each team member. Peer assessments and evidence often work well together, but this adds complexity.

Performance - this is the best way to assess expertise. Skills should be mapped to outcomes and over time outcomes will allow one to make inferences about actual expertise. This requires a lot of data though, and some fancy analytical tools. It is the gold standard.

Inference - AI’s can be used to assess performance. This can range from semantic AI’s that operate on inference networks (Ibbaka’s approach) to machine learning approaches that operate on large, very large, data sets. As more and more data becomes available this approach to skill assessment will come to dominate.

Of course these approaches are not mutually exclusive. A good skill and competency management program will likely begin with two or three of these (self assessment, peer assessment, manager assessment and expert assessment are common choices, tests are often added in as available, often through integrations with learning management systems). The approach to assessment is likely to mature over time as more data is collected. The long-term goal should be to get to Performance and then Inference.

How will the skill profiles evolve over time and stay current?

Skill profiles are not static. If they were we would stagnate and eventually be replaced. Skills need to be constantly growing. What are the dimensions of this growth?

New skills are added

Proficiency on skills increases

Skills are used in new roles and on new projects

New connections are created between skills

These four aspects of skill growth are how both individuals and organizations adapt, build resilience and move towards efficiency.

Given this, how do we keep skill profiles current? Annual performance reviews or skill surveys will not work. The world is much too dynamic for this. How does one make skill updating a regular thing, something that happens in the background but keeps data current?

There are three ways to do this, each of which reinforces the other.

Integrate with resource and project management systems. The Ibbaka AI can infer skills from these systems (remember that Ibbaka only suggests, people need to accept skills into their own profiles). Learning management systems and learning experience platforms can also provide suggestions as long as we remember that consuming learning content does not equal learning and is a long way from application and performance.

Connect skills to work and teams. Skills are most meaningful in the context of how they are used. Connecting skills to jobs, roles and teams is also a way to connect skills to performance. This is the key tactic.

Encourage conversations around skills and their application. One way we do this is by making it easy to suggest skills to other people. These suggestions are like small gifts we can make to each other. They also deepen skill insights as the people we work with often have a greater understanding of our skills than we do ourselves.

As skill profiles are updated over time, one can begin to see the direction of skill development for individuals, teams and whole organizations. As new skills emerge for specific roles, skill and competency models can be updated dynamically. This is the power of skill and competency management: deeper insights, accelerated development, superior results.