SaaS discounting practices and pricing

Steven Forth is a Managing Partner at Ibbaka. See his Skill Profile on Ibbaka Talio.

Discounting is a fact of life for most B2B companies. Yes, there are a small number of SaaS companies that have ‘no discounting ever’ policies and stick to them, but these companies are rare.

For an example of a company successfully executing a no discounting policy see “Why We Don't Offer Discounts At Chili Piper. Ever.” by Tom Rowe and the comments below.

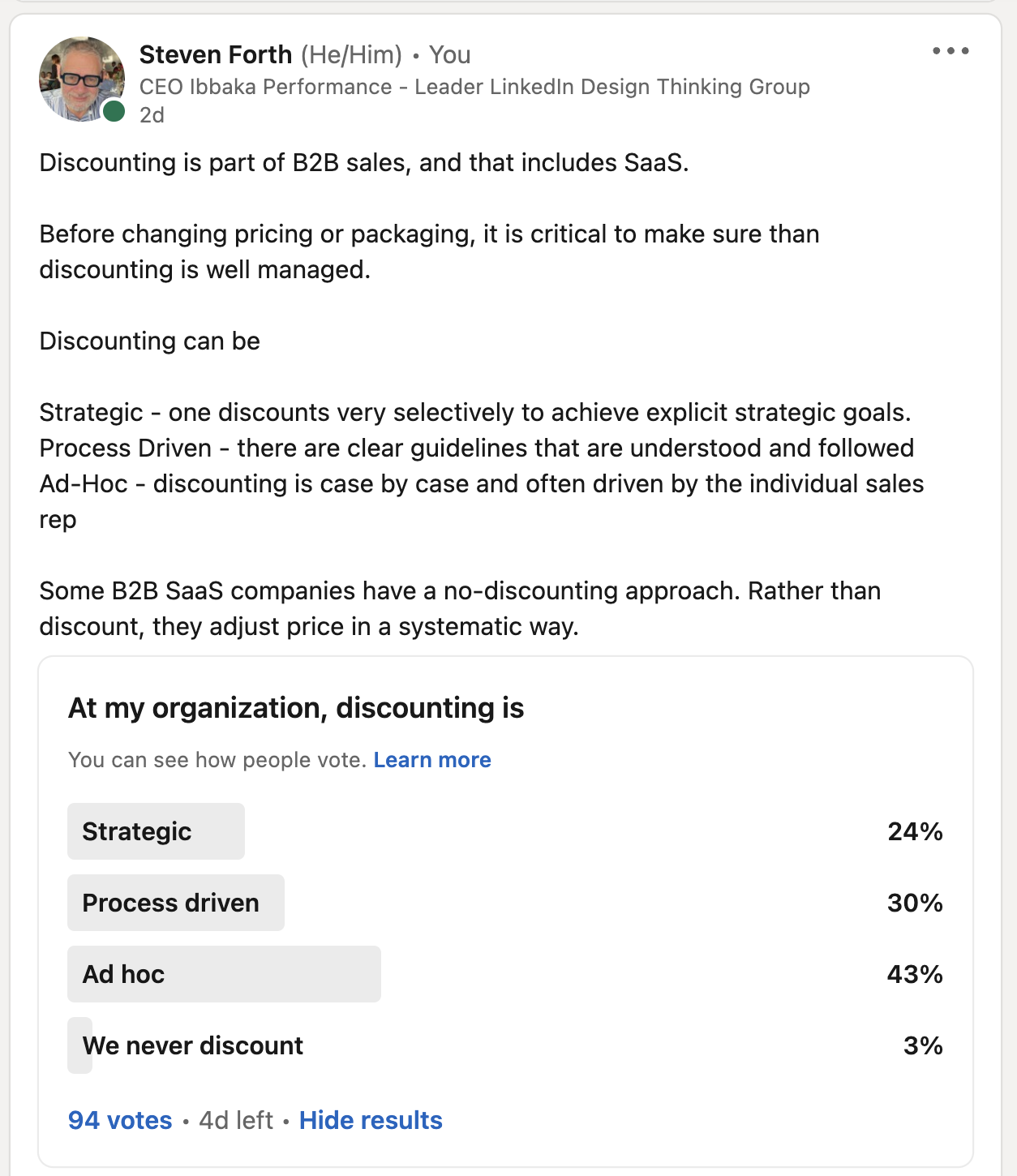

In a recent poll that Ibbaka posted to LinkedIn, we got the following responses (the poll was posted across the following groups: SaaStr, PDMA (Product Development Management Association), Software as a Service - SaaS Group, and the Professional Pricing Society. There were 237 responses altogether. Here are the results.

Here is the actual poll (this one is from the Professional Pricing Society LinkedIn Group).

We followed up with a number of respondents to get deeper insights into what was meant.

Strategic Discounting

Most people interpret this to mean discounting which is meant to win a strategic account, to win market share in a target segment, or to enter a new market.

Some people include managing churn as an example of strategic discounting (more on discounting, NRR, and churn is coming next week).

The key to successful strategic discounting is to regard the discount as an investment and do an ROI (Return on Investment) analysis on that investment. Many companies say that a discount is an investment, but don’t really treat it that way. There is no analysis of the scale of the investment and the expected return, and when there is there is seldom any follow-up to see if the return on the discount was realized.

Of the three people interviewed on this topic, only one actually does this in a formal way (and there is selection bias here, we reached out to this person as we knew that this is what they are doing).

If you consider your discounting a strategic investment, do you manage it that way?

There can be strategic reasons to discount, but is this more often camouflage for uncertainty about value and a need to drive ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) growth at any cost?

Process Driven Discounting

Companies executing process-driven discounting are operating with clear rules and making sure these rules are followed.

There are many ways to design a discounting process.

Most approaches involve setting guide rails for sales (they give salespeople some agency in setting discounts which are important). A floor and sometimes a ceiling is provided.

A related approach is to have a cascading level of approvals, where, for example, the salesperson can give a 5% discount, the sales manager a 20% discount, and discounts larger than this require formal executive approval.

The best practice is to document reasons for giving the discount in the CRM (Customer Relationship Management), CPQ (Configure Price Quote), or price management system. A typical taxonomy for this is as follows:

In Return for a Commitment

Longer Contract

Recommendation (Case Study, Referrals)

Volume

To Meet a Competitive Bid

To Satisfy a Requirement from Procurement

To Calibrate price to value (if for well-defined reasons the buyer will not get all of the designed value then a discount can be appropriate)

To Make a Strategic Investment (see above)

Sales compensation also needs to be part of the discounting process. This is worth a discussion of its own, but the basic thing to consider is the impact of discounting on margins. It can make sense for the sales commission as a percentage of the deal to go down along with discounts.

Ad Hoc Discounting

This is by far the most common form of discounting. The above figure of 43% is likely optimistic. Some companies that say they are executing strategic discounting also have a high level of ad-hoc discounting. The same is true of process-driven discounting. One can have a process, but is it followed?

The way to test for ad hoc discounting is with a price dispersion analysis. Define the factors that should be controlling price. Put them on a series of graphs. Calculate how much of the variation (dispersion) in observed prices can be accounted for by the pricing and discounting factors.

In the above figure ‘volume’ is only one of several variables that can be used in price dispersion analysis.

No Discounting

There are some companies who simply do not offer discounts. Chili Piper is a well-known example. Chili Piper is an inbound lead conversion and scheduling app. The reasons they give for not discounting are …

Faster sales cycles

Leverage the dark funnel (potential buyers who are researching your solution but who have not contacted you)

Discounts are not a one-time concession

Keep the books clean, and give yourself the freedom to strategize

Discounts don’t stay secret

A no-discount policy is more common in Product Led Growth companies, although these companies sometimes use discounts as part of sales campaigns. PLG companies are underrepresented in the poll data.

There are also enterprise companies that refuse to negotiate discounts. One of the strongest statements of this was something I overheard at a Professional Pricing Society conference.

“We are committed to fair and transparent pricing. Discounting goes against this. Giving a price to someone because they are a good negotiator is neither fair nor transparent.”

One way to address procurement’s concern about pricing and discounting is to offer a Most Favored Nation (MFN) clause, in which if a lower price is given to another company it will also be extended to anyone with the MFN clause in their contract. This protects procurement against your giving a better price to one of their competitors (a firing offense for a procurement officer). Doing this requires a lot of business discipline, and you have to make sure that the MFN clause compares like to like. MFN contracts can end up in court.

To execute on no discount pricing you need to have very well-designed pricing and packaging and to operate in a market that does not require a lot of configuration or customization. Not all companies can, or should, fit this pattern. But for those that can, a no-discounting approach can remove a friction point in sales.

Alternatives to price discounting

Sales often default to discounting because they do not have other tools to defend the price. If the only tool that pricing has is discounting then that is what they will use. There are other approaches.

Begin by positioning value. Always get a commitment to value before you negotiate the price.

Provide sales with value calculators and value stories and support them in using these tools.

Set up value gives that can be used instead of discounts

Functionality upgrades

Capacity upgrades

Extra services

Put a time limit on the discount (so that it only applies to the first part of the contract)

Offer a rebate instead of a discount (people are happier to get their money back rather than to receive a discount)

Managing discounting is a critical part of pricing.