Pricing for viral business models

By Steven Forth

One of the most powerful of all business models is one in which each user gains you more users. If you can achieve this and you are delivering sustainable value to your users, you have a big winner. The standard measure of virality is known as k, and the standard way of calculating it is given below. The equation and most of the ideas behind such self propagating systems come from epidemiology, and yes, from the study of how a virus spreads through a population.

k = (Number of Current Users x Number of Invitations Sent by Current Users x Percent Conversion Rate) / Number of Current Users

This is sometimes simplified to:

k = Number of Invitations Sent by Current Users x Percent Conversion Rate

These two formulas give the same value for k. The advantage of the latter is that it is simpler and focuses attention on the two metrics that matter. Do your current users invite additional users? Do those users accept the invitations?

There are other things to consider of course. The two most important things are (i) what is the time cycle? and (ii) what is the churn rate? It makes a big difference to growth if the time cycle is one week, one month or one year. Also, if users convert but have a high churn rate (if many users fail to renew) then a high k is not all that helpful.

One can sharpen this equation by specifying the time unit and seeing how k changes for different time units. In some cases, a user will only invite new people in the first week or not at all, in which case k week = k month = k year. While in other cases a user continues to invite in new users over time so that k week < k month < k year.

One can easily adjust for churn by multiplying k by (1 - churn), being careful to use the same time scale to calculate k and churn.

So what does all this have to do with pricing? It all comes back to value and differentiated value, as is the case with all pricing that does not involve commodities. Let's look at each variable in the viral equation using a value lens.

Number of Invitations Sent by Current Users

Why would a user invite another user to use your software? Just because they like it? Probably not. There has to be some more tangible value. As we know, value has emotional and economic dimensions and it is hard to get traction, at least in B2B, without some of both. If you expect people to invite their networks into your application, they need to be confident that they are getting value and that the people they invite will get value. This value needs to be part of the natural outcome of using the software and not some sort of external incentive like a discount in return for making referrals. External incentives can help of course, and they have become common. But they only really work if there is real value for both parties. Below we look at how DropBox struck a balance with this.

The critical business question to ask is,

How does the user get more value by having other users join the system?

Percent Conversion Rate

Getting users to send out invitations is necessary but not sufficient. The invitees have to accept the invitation. Why should they? Is the value proposition clear to them? Is there some advantage to accepting this invitation rather than that of another user? (Perhaps User A can provide more value than User B, and if this is clearly communicated they are more likely to respond to User A than User B. We often join clubs based not on the club's facilities but on who the other members of the club are.)

The critical business questions to ask are,

How do the new users get value by joining?

Is there a difference between the conversion rates for different users? If so, why?

Churn

It costs money to attract and bring on users, so you want to keep them. You will only do this if you provide value. This is where customer journey maps with the three value layers, are so important. (See Value creation and communication across the customer journey.) It is critical that value is being communicated and delivered in the months and weeks before the renewal decision is made.

Time scale or Cadence

Marketers often do not spend enough time thinking about cycle times or cadence. Your business model looks very different if your customers are sending out an invitation after one week rather than one month. The customer journey map is useful here as well. When in the customer journey does a customer get value from inviting in new users? Can you move this forward so that they get the value earlier? Is there a natural rhythm that you can get rolling that would make it meaningful to invite in new users on a regular basis?

Dropbox as an Example

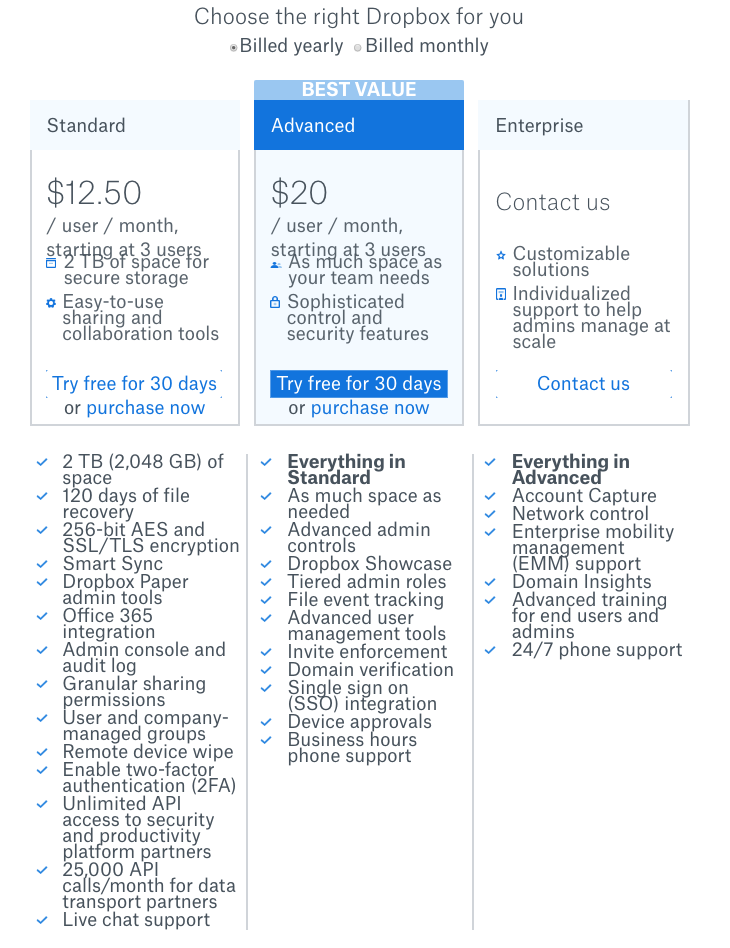

Dropbox is an almost perfect example of a viral business model for B2B. The core value propositions of Dropbox are (i) save money on storage and (ii) better collaboration on documents. It is the second that drives virality, but the two interact in interesting ways. Take some time to study the Dropbox pricing page and look for the ways in which it encourages virality. Look for the words 'user' or 'team' and 'sharing' or 'collaboration.'

Collaboration is the driver of the DropBox business model. You can think of it as 'store once, charge many times.' If you share a document with me on DropBox, it is only stored once but we both pay for it. The angel fund we work with (E-Fund) uses DropBox for due diligence and I have had to upgrade my account several times to cover all the documents generated in the due diligence process . Look at the above pricing sheet. There is a storage fence for standard (a generous 2 terabytes) but no limits on storage at the Advanced tier. These fences are guiding heavy users into the advanced tier.

LinkedIn and metcalfe's law

One of the most successful viral businesses is LinkedIn. It is a great example of the value of a network as described in Metcalfe's Law. LinkedIn is of limited value to one user, but the value grows with N (the number of active users) such that

Value = N * (N-1) /2 which approximates to N squared.

In networks where the more connected nodes are more valuable, which is most business and social networks, the relationship between Value and N is closer to n × log n . In any case, it is the number of users that is driving the value. (If you want to go deeper into this, check out the research comparing the Chinese network Tencent and Facebook - Tencent and Facebook Data Validate Metcalfe's Law by Xing-Zhou Zhang, Jing-Jie and LiuZhi-Wei Xu in the March 2015 issue of the Journal of Science and Technology.

This is why LinkedIn is free. Every new active user adds to the value of the network.

Image from Wikipedia article Metcalfe's Law

LinkedIn charges for people who get exceptional value from its network. Some of these are Premium users (I pay for a Premium account), others are recruiters, sales and marketing, with human resources and talent management being added.

Each of these have very different value metrics and thus a different pricing model. As a Premium User I am mostly interested in getting more value from my own account. The more people I am connected with the more value my Premium Account is to me. The more active I am on LinkedIn the more valuable my account is to me. LinkedIn encourages me to grow my own network and to be as active as possible. This increases the value LinkedIn provides me and my Willingness to Pay (WTP).

The value proposition for Recruiters is very different. Recruiters want to identify and reach out to other people. They benefit more from people having complete profiles than from user activity. They need access, good search, and tools to manage and filter search results and put them into their applicant tracking systems. As Recruiters get paid for filling positions, the value proposition is very clear. That is why LinkedIn was initially focused on optimizing this business model.

Recruiters and Premium users play very different roles in the LinkedIn model. It is the Premium users that drive activity and generate the invites that push up K. The Recruiters feed on the value created by Users and Premium Users, though some would say that the Recruiters make LinkedIn more attractive as many people are on LinkedIn or update their profiles when they want to find new jobs.

In any case, think about K as you design your pricing strategy. Here is a simple checklist.

Do current users get value when new users join?

When do the current users experience the value of having new users join?

When do the new users experience the value of joining through an invitation?

(Dropbox is so powerful because the value is immediate.)

Are invitations from some users more valuable to the invitee than other users?

Does your pricing model encourage or discourage invitations?

Does your pricing model encourage or discourage acceptance of the invitation?

What is the cadence of invitations and can it be accelerated?

Are users experiencing value in the period before renewal?